Ebook Download The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny

Based upon the The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny information that we provide, you might not be so confused to be right here and also to be participant. Get now the soft file of this book The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny and also save it to be all yours. You saving could lead you to evoke the simplicity of you in reading this book The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny Also this is kinds of soft documents. You could actually make better opportunity to obtain this The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny as the advised book to read.

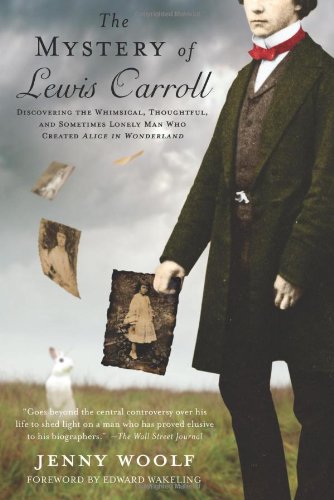

The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny

Ebook Download The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny

The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny. A job may obligate you to consistently enrich the understanding as well as encounter. When you have no enough time to boost it straight, you could get the encounter as well as understanding from reading guide. As everyone knows, book The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny is preferred as the window to open up the globe. It suggests that reading publication The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny will give you a new means to find every little thing that you need. As guide that we will supply right here, The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny

The factor of why you can obtain and get this The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny quicker is that this is the book in soft data kind. You could read the books The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny wherever you really want also you are in the bus, workplace, residence, and various other areas. Yet, you might not have to relocate or bring the book The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny print anywhere you go. So, you won't have heavier bag to lug. This is why your choice making better concept of reading The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny is really valuable from this situation.

Understanding the method how to get this book The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny is likewise important. You have actually remained in right site to begin getting this details. Obtain the The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny link that we supply here as well as visit the link. You could get the book The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny or get it as quickly as possible. You could swiftly download this The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny after obtaining bargain. So, when you require the book rapidly, you could straight receive it. It's so easy therefore fats, right? You have to choose to through this.

Merely connect your device computer system or gadget to the internet linking. Get the contemporary technology making your downloading and install The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny completed. Even you do not want to read, you can directly shut guide soft file and also open The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny it later on. You can likewise quickly get the book almost everywhere, considering that The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny it is in your gizmo. Or when being in the office, this The Mystery Of Lewis Carroll: Discovering The Whimsical, Thoughtful, And Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice In Wonderland", By Jenny is additionally advised to check out in your computer system device.

A new biography of Lewis Carroll, just in time for the release of Tim Burton’s all-star Alice in Wonderland

Lewis Carroll was brilliant, secretive and self contradictory. He reveled in double meanings and puzzles, in his fiction and his life. Jenny Woolf’s The Mystery of Lewis Carroll shines a new light on the creator of Alice In Wonderland and brings to life this fascinating, but sometimes exasperating human being whom some have tried to hide. Using rarely-seen and recently discovered sources, such as Carroll’s accounts ledger and unpublished correspondence with the “real” Alice’s family, Woolf sets Lewis Carroll firmly in the context of the English Victorian age and answers many intriguing questions about the man who wrote the Alice books, such as: • Was it Alice or her older sister that caused him to break with the Liddell family? • How true is the gossip about pedophilia and certain adult women that followed him? • How true is the “romantic secret” which many think ruined Carroll’s personal life? • Who caused Carroll major financial trouble and why did Carroll successfully conceal that person’s identity and actions? Woolf answers these and other questions to bring readers yet another look at one of the most elusive English writers the world has known.- Sales Rank: #900741 in Books

- Published on: 2010-02-02

- Released on: 2010-02-02

- Original language: English

- Number of items: 1

- Dimensions: 9.56" h x 1.16" w x 6.49" l, 1.18 pounds

- Binding: Hardcover

- 336 pages

Review

“Goes beyond the central controversy over his life to shed light on a man who has proved elusive to his biographers.” ―Wall Street Journal

“Engaging...Woolf writes with affection as well as admiration for the man revealed by her research.” ―Michael Dirda, The Washington Post Book World

About the Author

JENNY WOOLF has written for The Sunday Times Magazine (UK), Reader’s Digest, and Islands and has reviewed children’s literature for Punch. She is author of Lewis Carroll in His Own Account. She lives in England.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

1

‘My Father and Mother were

honest though poor …’

Family

…An island-farm – broad seas of corn

Stirred by the wandering breath of morn –

The happy spot where I was born.

‘Faces in the Fire’

It is a curious thing that Lewis Carroll, so closely associated with Victorian childhood, hardly ever spoke about his own childhood. Not only did he refrain from discussing his youth, but almost nobody else left personal memories of it either. His brothers and sisters supplied only a few carefully edited recollections of him as a boy. Those family letters which survive hardly refer to him as an individual.

His arrival in the world, though, received a few lines of public notice. It was the tradition among the middle and upper classes to announce the birth of offspring in The Times of London. So it was that on 31 January 1832 the newspaper carried an announcement of the birth of the baby who became Lewis Carroll.

Carroll’s real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, and he had been born a few days earlier, on 27 January 1832. He was the oldest son and the third child of the Revd Charles Dodgson and his wife (and first cousin), Frances. His birthplace was a small parsonage in Morphany Lane in the village of Daresbury, Cheshire, where his father was perpetual curate. There had been two Dodgson sisters before him and there would be eight more children after him, following at a rate of one every year or two. Every one of the eleven survived, and throughout Carroll’s whole life he would be a vital and valued member of this huge and self-contained group. Always in his background, always in touch, his siblings remained of great significance to him throughout his life.

Not only the eleven children, but the family’s numerous aunts, uncles and cousins were close-knit. They all knew that upon the Revd Dodgson’s death, Carroll, as the oldest son, would become the head of the family. If any of the brothers and sisters needed help with their problems, it was to him that they would go, no matter how old they might be. Carroll’s whole existence was to be spent in the full knowledge and awareness of this large responsibility.

The England where the Dodgson family grew up is still sometimes portrayed in idealized form on traditional Christmas cards. It seems like a jovial land of Mr. Pickwick, of stagecoaches and poke bonnets and roast beef, of simple country folk and inns and ale. The reality, of course, was less comfortable. Huge technological and social changes were under way, and public attitudes had yet to catch up with them. As the Dodgsons’ first son greeted the world, slavery was legal, cholera was rife in cities, Roman Catholics were barred from Parliament, and tiny children were being worked to death in factories. Married women had no legal right to keep their own earnings, and public executions were still a popular form of entertainment.

Such repressive, sometimes savage attitudes towards women, children, religion and crime would take many years to change. Whether or not Carroll accepted them (and mostly he did not), these attitudes shaped him and his contemporaries and provided the intellectual and social background to their early lives.

Daresbury, where Carroll spent the early years of his life, was then a pleasant small village with a population of around 150 souls, at the centre of a scattered parish in flat, lush countryside. The parsonage was some distance both from the village and the church, and it was so countrified that even the passing of a cart on the road was said to be a matter of great interest for the children.1

The Revd Dodgson, though well bred and well read, was however not well off. He was a brilliant scholar who had obtained a double first at Christ Church, yet as a mere perpetual curate he was ill-paid and doing a job far below his intellectual capacity. Without influential people to lobby for him, there was little he could do but make the best of it, and his situation was a matter of some pain to him and his friends. His poverty and enforced lack of status would not have been lost on his eldest son.

The family’s life in Daresbury was very rural. They kept livestock and grew some of their own food, but of course, living in a Georgian country house and growing one’s own vegetables was not quite the charming existence that it might be today. Both parents made the best of their lives with Christian cheerfulness, and if the Dodgson siblings’ tight-knit, cooperative and upright adulthood is anything to go by, their youth was orderly, austerely religious, affectionate and generally happy. The Revd Dodgson worked hard at ministering to his widely dispersed flock, and took in extra pupils to help bring in a few extra shillings to feed, clothe and educate the family. His wife searched endlessly for inexpensive ways to manage the household and her brood of growing children, as her stream of dashingly underlined letters to her sister eloquently testifies:

… Loui I have only got the llama Wool High Dress she had last Winter & for Carry & Mary I have got nothing for the morning – the few High Dresses they had last Winter are quite done – their Pelisses must also pass down to the younger ones (the two smallest being wanted to make one for darling Edwin … Can I get wrong in choosing the above for them in Darlington? they would be less expensive there I should think …2

The Dodgsons stayed in Cheshire until 1843, when Carroll was eleven, after which they moved to Croft-on-Tees, north Yorkshire, where Carroll’s father had gained a well-deserved promotion to rector. In 1852, he was made residentiary canon of the ancient cathedral at Ripon, Yorkshire, and after that, he and his family spent time in Ripon as well as at Croft.

There is but one recorded remark from Carroll about himself as a child, contained in a letter to a lady friend, and it is brief. He wrote, during a diatribe about how he disliked boys, that he had been a ‘simply detestable’ little boy.3 He was probably joking, but, as a boy, detestable or not, he hardly figures individually in preserved family letters and papers. Any family friends who remembered him chose not to come forward with their memories of his youth, and even the neighbours had almost nothing to say.

In fact, since Carroll did not attend school until he was 12 years old, it can fairly be said that he had little significant childhood existence outside his large, extended family. From the very start, he was one of a group, not as much of an individual in his own right as someone from a smaller family would have been. He had to take his place, wait his turn, and join in.

Letters still in the Dodgson family’s possession, telling relatives how glad and happy their children made them, show that both parents delighted in their family life. In the very busy but well-organized household, the offspring were distinguished by their initials and referred to mainly as ‘treasures’ and ‘darlings’. There is a surviving letter from 1837, which Carroll, then about five, ‘wrote’, with his hand guided by an adult. Couched in baby talk, it sends a ‘kitt’ (kiss) from ‘Charlie with the horn of hair’, its existence showing that adults in his life doted upon his babyish quirks of speech and his infant curls.4

The few reminiscences of him which his nephew Stuart Collingwood coaxed from Carroll’s brothers and sisters when writing his biography, present a quaint, charitable and clever child, demanding to know what logarithms were, and making personal pets of snails and toads and worms. Perhaps understandably, the book is not very objective yet, within the limits of presenting a conventional picture of his uncle, Collingwood tried hard to show him as the quirky human being he essentially was. He had been a child, he said, who seemed ‘to have actually lived in that charming “Wonderland” which he afterwards described’.5

As he grew older, Carroll emerged as the family entertainer, involving his brothers and sisters in vast imaginative games in their huge garden. Railways being the latest thing at the time, he made a train from a wheelbarrow, a barrel and a truck. It would carry its young passengers from one ‘station’ in the rectory grounds to another, in accordance with a long and deliberately ridiculous list of railway regulations that he concocted for them. He learned sleight-of-hand and dressed up to amuse his siblings with magic shows. He helped make a toy theatre – he was good with his hands – and wrote puppet plays which he and the older ones performed. They also wrote and illustrated several family magazines under his guidance, and when he was away from home he wrote them long, loving, and entertaining letters.

One of these letters, written in his twenties and addressed to his youngest brother and sister, then aged 12 and 9, has survived. He had just become a tutor at Christ Church, and it gives an account almost worthy of the Marx Brothers of how Oxford lectures were supposedly conducted via a sort of Chinese whispers system through doors and all along corridors:

Tutor. ‘What is twice three?’

Scout. ‘What’s a rice tree?’

Sub-Scout. ‘When is ice free?’

Sub-sub-Scout. ‘What’s a nice fee?’

Pupil (timidly). ‘Half a guinea!’

Sub-sub-Scout. ‘Can’t forge any!’

Sub-Scout. ‘Ho for Jinny!’

Scout. ‘Don’t be a ninny!’

Tutor (looks offended) …’6

Family life seems to have been very harmonious, with no suggestion that any family members were left out or badly treated by the others, although Skeffington, the second brother, may have had slight learning difficulties and seems to have been a worry at times.

Viewed from a century-and-a-half away, the inter-relationships and personalities of the family members have, of course, mostly faded to obscurity. But because they were such a major influence on Carroll, it is worth taking a quick look at what is known about his sisters, his brothers and other close family members.

Just as his family rarely discussed him with outsiders, so Carroll spoke little to outsiders about them. No descriptions remain of any of them as children, but in adulthood Carroll sometimes referred to his sisters generally as the ‘sisterhood’. The ‘sisterhood’ were intelligent women who were generally acknowledged to share a strong sense of duty and family interdependence. They did a great deal of charitable work, all had a good sense of humour and were fond of children. In later life, he regarded their home in Guildford as his home, too, and he spent a good deal of time there.

The two oldest sisters were Frances (Fanny) and Elizabeth, respectively four and two years older than him. Fanny was said to be sensible and capable, artistic, musical, fond of flowers and devoutly religious, with a flair for looking after the sick and helpless.

Carroll seems to have particularly confided in the second sister, Elizabeth. He told her of his joys and sorrows, and she was probably the one who mothered him most. She was extremely fond of children, and always yearned to look after babies. A touching little sheet of paper has survived on which young Elizabeth dotingly copied down some of the chit-chat of her small brothers and sisters playing in the nursery.

The third sister, Caroline, was very shy and reclusive, and many early family letters mention unspecified anxieties about her. She hardly went out, and suffered particularly badly from one of the speech defects which plagued the family.

The only one of the seven daughters to marry was the fourth, Mary. She was artistic and strongly religious. She was in her mid-thirties when she married shortly after her father’s death, and a Dodgson family descendant has suggested that it may have been a relief that someone had come forward to look after Mary, leaving one less mouth to feed.7 Mary may have had a hard life, for her husband was often ill. She obviously missed her sisters, for she returned to live with them after his death, and one of her two children, Stuart Collingwood, became the family biographer.

The fifth daughter, Louisa, survived all her brothers and sisters, dying at the age of 90. She had become an invalid, which probably gave her the leisure to pursue her keen interest in mathematics, which sometimes occupied her mind so much that she did not notice what was going on around her.

The sixth daughter, Margaret, also liked mathematics and backgammon, and helped a good deal with the Croft National School, which her father had established in order to educate local poor children. Margaret does not sound particularly unconventional, but the youngest daughter, Henrietta, certainly was. By the time Henrietta was middle-aged, she had managed to inherit and keep enough money to set up a modest household independently from her sisters, although she did remain in close touch with everyone. She moved to Brighton, where she lived with an ancient maidservant and a menagerie of cats.8

Tall and gaunt, Henrietta generated several family stories about her eccentricities. There was the portable stove she brought along when visiting relatives, to enable her to fry sausages in her bedroom. There was the time she once became so involved with singing hymns on the train with fellow passengers that she missed her stop, and on another occasion she accidentally took an alarm clock to church one day instead of her prayer book. Carroll often visited Henrietta in Brighton, and he sometimes took his young friends along, too. One such was Katie Lucy, aged 17, who noted in her diary, ‘I like her. I think she is like him.’9

Of the four brothers, Edwin, the youngest of all the children, felt called to become a missionary and spent time in Africa and Tristan da Cunha. His work was at times very hard and discouraging, and his descriptions of his extremely difficult life in Tristan make it clear that, for Edwin, human love and pleasure were not part of his self-denying life plan. He never married and his last years were spent as an invalid.

The third son and seventh child, Wilfred, was lively minded, humorous and clever. He loved the outdoors and rejected academia, breaking from the family clerical tradition to become an estate manager. He was a successful businessman, married his childhood sweetheart in 1871, and had nine children.

The second son and sixth child, Skeffington, had difficulty with academic work, and was forgetful and emotional. He married late in life after a rather turbulent clerical career, and settled in Vowchurch, Herefordshire. There, he lived as an impoverished vicar, pursuing his passionate hobby of fishing. He was often teased for his eccentricity by his rustic parishioners, but his wife was charming and clever and the family was very happy. He was a strict but beloved father to his three surviving children.

The fact that only three of the Dodgsons’ eleven children married has sometimes attracted comment, but this is not necessarily a sign that the family had issues with the idea of marriage. Carroll and Edwin both had jobs that made marriage difficult, and the girls probably did not meet enough people or socialize enough for all of them to find husbands. Like the vast majority of young women of their class, they had a very restricted existence. They could not attend university, nor have careers. If of marriageable age, they could not go out alone to make friends outside the extended family circle, nor speak to men they did not know. Carroll never danced, and always avoided dancing, so it is also possible that there were family restrictions on this form of social entertainment.

An aged neighbour, speaking at the time of Carroll’s centenary celebrations in the 1930s, knew the daughters before 1868, when they would have been in their twenties and thirties, and remarked on how plain their clothes were and how self-sacrificing their lives. As one family descendant wryly observed after considering their photographs, they seem to have been dressed in ‘last year’s curtains, with room allowed for growth!’10

Apart from Carroll, who earned his own living, the Revd Dodgson supported all his children during his lifetime, and scraped enough money to leave a trust fund to allow the sisters to live together after his death with modest financial independence. For them, as for any women with minds and means of their own, marriage was not necessarily much of an attraction. A wife had to surrender everything she owned or earned to her husband and put herself under his control. So apart from the prospect of motherhood – a mixed blessing – their father’s consideration of them meant that there was no practical need for the sisters to marry.

Despite, or perhaps because of the lack of outside contacts, the siblings’ closeness and interdependence meant that none of them ever needed to feel lonely, unwanted or out of place, so there would be little reason to marry for companionship. There was always someone to remember their birthdays, always someone to share a joke with or drop in and see, and always someone with whom to spend Christmas. Even Edwin wrote long, long letters to his family as he battled the windy deprivations of Tristan, and the sisters faithfully copied these long letters out and circulated them for other family members to read.

Excerpted from The Mystery of Lewis Carroll by .

Copyright 2010 by Jenny Woolf.

Published in February 2010 by St. Martin’s Press.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

Most helpful customer reviews

51 of 54 people found the following review helpful.

The Likeable, Peculiar Man from Wonderland

By Rob Hardy

It has become part of our received knowledge that Lewis Carroll, author of the Alice books, liked being with little girls, and liked photographing little girls without their clothes, and that for all we may enjoy Alice's adventures, we have to wince at their author's being a pedophile. I have heard a presenter classify him in that category in a medical presentation on child abuse, for instance. I want to put quickly into this review that such accusations are not true, even though clearing them away is only one of the many insights within _The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created Alice in Wonderland_ (St. Martin's Press) by Jenny Woolf. Woolf is a reviewer of children's literature, and has written about Carroll before. There are plenty of other biographies of the famous author, but she says, "The more closely Lewis Carroll is studied, the more he seems to slide quietly away." (She doesn't mention it, but this is rather like Alice trying to put her hands on items on the shelves of the sheep's shop.) Some of the problem is that the original source documents we would like to read about Carroll have disappeared, like diaries from certain years that seem to have been deliberately cleared away by his family after his death. Part of the problem is that very few of the people that knew him, even close friends, wrote about him or talked to biographers after he was gone. Part of the problem is that there was gossip about Carroll while he was alive (and the gossip was about subjects other than his relationships with little girls). Part of the problem is that his times and his locale in academic Oxford were peculiar viewed from our own time. And a big part of the problem is that he was very peculiar himself. Not naughty, not sociopathic; just very odd, an oddness you might expect of the author of Wonderland. Woolf's thoughtful volume is not a chronological biography, but an examination of different aspects of Carroll's life, aspects which give a satisfyingly full portrait.

The events in Carroll's life were not complicated or exciting, and we would not care anything about him if he had not written _Alice in Wonderland_ (1865) followed by _Through the Looking-Glass_ (1871). The lack of a moral to the tales is regarded by some as a strike against the author, evidence that he was bad in other ways. Those who get carried away by such thinking accuse him of being an opium addict or being Jack the Ripper. The more moderate of the calumniators say that he was having an affair with Alice's mother, or with Alice's governess, or with Alice's elder sister, or, of course, with Alice herself. Part of the "evidence" against Carroll is that he took pictures of naked little girls. We think this shocking now, and even parents have been summoned to court when pictures of their children sunbathing show up at the developers, but Carroll and his proper Victorian contemporaries held a different view. His fascination with little girls was, in fact, a rejection of sexuality - they were seen as non-sexual and pure. He was loved by his child friends, and it gave him an emotional foundation without any hint of carnality. Naked girls were not at all the main theme of his photography; of nearly 3,000 negatives this enthusiastic hobbyist took, around 1% are of children partially or completely nude. All of his pictures of children were taken when the children wanted to, and when the parents consented, and anyone had a veto. "There are no assertions, no reports of gossip, and no hints or suggestions that any parent of any young child portrayed nude by Carroll felt threatened by anything he did," says Woolf. "Nor did any of the children themselves, after they grew up, suggest that they had been upset by their encounters with him: the opposite seems to have been the case."

There are those who charge that Carroll was too innocent to understand the pedophilic crimes he was committing, but Woolf is justifiably proud of a scoop she has on all other Carroll biographers: his bank account, which she discovered in a financial archive, and which she calls "the only major document about him which is both factual and completely unaltered." Carroll did know of the problem of child exploitation, and supported organizations like The Reformatory and Refuge Union, The Society for the Suppression of Vice, and The Metropolitan Association for Befriending Young Servants. He did not boast of such support, nor can the case be made that singling out such causes indicates a guilty conscience, for Woolf goes on to show that they were a mere part of a larger system of giving to many good causes. It was said that Carroll was rich from his books, and they did produce a respectable income, but he was rather busy giving it away to charities and as support for family and friends. He paid little attention to material wealth, and specified when he died that he was to have the cheapest of funerals "consistent with dignity." He was no saint; he was exasperatingly fussy with his contemporaries, and he showed little interest in what ought to have been his life's work, teaching math to undergraduates. He did have many adult friends, and that they were of less emotional support to him than were his child friends is decidedly peculiar, but far from criminal. Woolf does more than debunking the pedophilia claims, taking chapter-by-chapter views of Carroll's life at Oxford, family relationships, literary life, and more. Such an approach gives a full picture of the strange and likeable man who gave us the imperishable Alice books and whose life needs no apologies.

0 of 0 people found the following review helpful.

Very enlightening

By B. J. Vasilik

Very interesting. Lots of research went into this book. Well done.

43 of 48 people found the following review helpful.

An in depth look at the character of Lewis Carroll.

By Jonathan Wilkin

Having read many other books about Lewis Carroll, I thought this was excellent. It was very easy to read and I thought the theories were all reasonable, and made use of the latest information avialable. The actual 8 page "Personal Conclusion" did seem a bit disjointed and rushed for some reason, but this did not detract from the whole. This book focuses in on the innner man, his motivations and true character. It makes use of the facinating new discovery of Lewis Carroll's bank account which was recently found in the archives of the Barclay's Bank. One thing this clearly reveals is what a charitable man he truly was, with a deep concern especially for women and children who had fallen on hard times in the streets of London. This book would be well to read in conjunction with Morton Cohen's biography which tries to give a much more historical look at the man; going into detail about all of the names and places and dates surrounding the man. But this book is much more pleasant to read and gives you a quick glance into the phyche of a very private man; a most beloved friend to dozen's of children, brother to seven sisters and three brothers, and famous author of children's books.

The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny PDF

The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny EPub

The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny Doc

The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny iBooks

The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny rtf

The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny Mobipocket

The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created "Alice in Wonderland", by Jenny Kindle

No comments:

Post a Comment